It really depends on what you call a radical? Here’s an example with four or five ‘radicals’ (or components, rather), even if some are repeated: 疆 (きょう). It’s probably not on WK, and it’s also probably not very common (in Japanese anyway; I learnt it in Chinese, and I haven’t seen it ‘in the wild’ in Japanese yet), but I’m just raising it for the sake of discussion. Among common, everyday kanji, you might say that 朝 is a combination of 2十, 1日 and 1月, or simply of 龺and 月. (To be honest, I have no idea what exactly 龺means. Apparently it represents the sun in the midst of grass in 朝.)

Anyway…

While learning Chinese while growing up, and even now, when I encounter new kanji, I look out for components that I already know as kanji (because those usually form bigger blocks). Thereafter, I remember the kanji based on the ‘sub-kanji’ I recognise. The rest of my ‘strategy’ tends to involve knowing how to write kanji though, since that helps me remember the position of the components based on their order of appearance in the written form, and I tend to kinda just ‘make’ myself remember the reading or the meaning (ideally both) based on something in the kanji, like how it looks.

As an example… OK, in order to remember 竈 (かまど, which shouldn’t be on WK), I remembered that the bottom component is something like ’turtle’ (亀, which used to be 龜 – I know some of the traditional kanji forms, which helps with stuff like this. Truth is though, the bottom component is actually 黽, which isn’t ‘turtle’ at all), then I noticed the 土 inside it, which means ‘earth’. That makes sense because 竈 refers to a traditional wood/coal stove made of bricks/earth, or a hearth. I know that the thing at the top is basically a small 穴: you could say that’s the ‘cave/hole’ radical, which makes sense as well because you need a hole in the wall to put firewood in. Weird stuff like that. I don’t come up with all this consciously. Some components just seem more obvious/sensible, and I use them to help me.

I think the original mnemonic for 掃 used to contain four components: wolverine + cloth + hand + 冖 (IDK what WK calls it, and I can’t name it in Chinese either). That comes pretty close to five ‘radicals’, and is probably an excessive breakdown, even if it’s not hugely problematic since the components are relatively simple. I can’t think of any kanji with more than four components that might appear on WK though, aside from 鬱, which you’ve already mentioned.

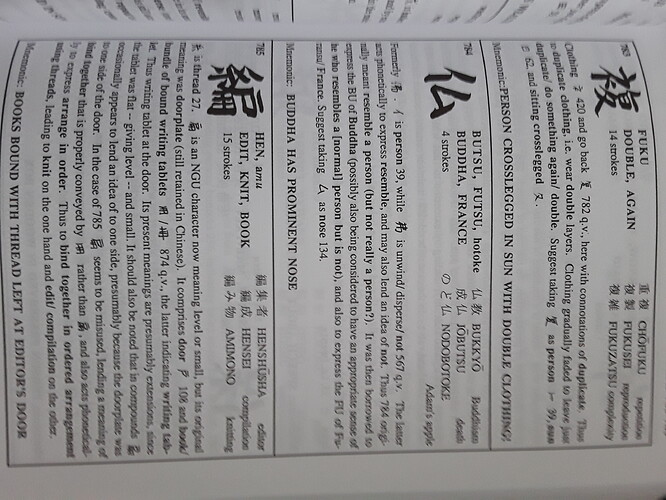

Here’s to hoping that @cringe knows of some in English, because everything I’m aware of is written in Chinese or Japanese. I mean, popular kanji courses outside of WK like ‘Remembering the Kanji’, ‘The Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course’ or ‘Essential Kanji’ generally have at least a bit of etymology in them, but not all of it is accurate or serious, since some of it is just there for the sake of helping people remember. The one resource I do know of is http://www.visualkanji.com. Not sure how good it is though, regardless of the author’s credentials, because I don’t know if she’s an etymology specialist. Another option would be to look at Kayo-sensei (aka @Kayoshodo) on Twitter, because she occasionally posts stuff about kanji origins, in addition to lists of common words and writing tips. She’s a Japanese calligrapher, but she posts in English. I don’t always agree with what’s said by these sources about etymology, but as Kayo-sensei says, there are multiple theories, and since most of my theories come from Chinese sources… well, perhaps some disagreement is to be expected.